|

|

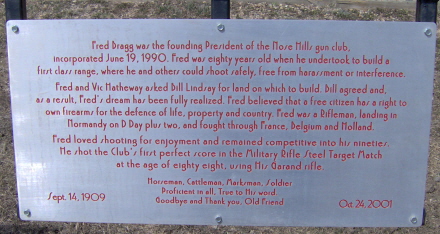

Fred Bragg

The following is an article taken from Shotgun News, written by one of our founding members, Vic Hatheway, about Fred Bragg.

If

you think you can't build a range, consider this ...

Dear

Fred,

This

is about another Fred, a man who can serve as a good model for all of us. I'll

do my best to properly honor one of the most modest men I ever knew. There are

so many blanks in his story, but I suppose he talked more to me than to anyone

else living around here. I'm proud to give you all that I DO have. I hope I get

it right, for his memory's sake. I did not meet this fine gentleman until he was

eighty.

Fred was born in Blue Earth County, Minnesota, Sept. 14, 1909. It is locally

believed that his family brought him as a baby to the country around Brooks,

Alberta. He mentioned a few times that he had been a young man there.

He grew up cowboying. What little formal education he received was massively

augmented by always having a book or two in his saddlebags. He read extensively

through the long winters, in line shacks and bunkhouses. At that time, without

any guidance beyond pictures in dime novels, he taught himself to shoot well.

Cartridges were very expensive on a young cowboy's wages, and he did not like to

waste them. A modern hand gunner would grin to see him shoot his .45LC Ruger

revolvers in his later years. His stance was straight out of the 1880's, knees

slightly bent, the off hand tucked in a back pocket, the shooting arm slightly

bent. (When arthritis crippled his left hand, he transitioned to shooting

right-handed, in his eighties.) The grins would quickly disappear from the

scoffing faces, as the man was deadly accurate out beyond one hundred yards,

one-handed!

With that sort of background, Fred was never far from the cowboy life. His

saddles were on racks in his bachelor living room, and in his later life he was

always ready to help a neighbor move some cattle. He was much respected for his

abilities on a cutting horse, or in roping. He could shovel more dirt or string

more wire than youngsters a third his age, and do it longer. The man was built

out of whipcord and whang leather, as they used to say.

The Depression hit the Prairies exceedingly hard, and the Dirty Thirties Dust

Bowl was something Fred didn't like to talk about at any length. The look on his

face gave an inkling of how hard it had been on him. In his late twenties he

joined a Canadian Army Militia unit for a little extra survival money and free

ammunition. He said uniforms were never complete: an army jacket and blue jeans

was a common outfit. No boots were issued, and he bitterly recalled

square-bashing in cowboy boots! He always grinned when he remembered that he was

the only man in the (eight-man) unit issued a heavy overcoat one winter!

In September of 1939, Britain declared war on Hitler's Germany. Canada, the

loyal Dominion, instantly followed. Fred saw the whole thing as a chance to

escape the drudgery of his isolated life, have three squares a day, a bed off

the ground, and a little adventure on the side. He enlisted in the Army before

the war was many weeks old, traveling mostly on foot to Calgary to do so. When

he did get a ride, it was in what was called a "Bennett Buggy" or an

"Aberhardt Wagon": a horse-drawn Model T Ford named for the Canadian

Prime Minister and Alberta Premier, the common Depression-era vehicle of the

times, as no one had cash to spend on gasoline.

Put on a train in Calgary, he chugged his way to the training camps of the East,

and ended up in, of all things, the Artillery. He was troop-shipped across the

U-Boat infested Atlantic to England, (his convoy lost a few ships), arriving in

1941 for more training. He was in the Artillery, but of course there were almost

no guns. He said so many gun crews trained on the same 25-pounder that the

breech, traverse and elevation mechanisms were almost destroyed. Of course, they

never got to actually FIRE the thing! Fred said that the fact there were no

shells available saved his life, as it probably would have blown up. But

dragging that piece around in English rain and mud decided him on trying for a

better life.

After the debacle of Dieppe, a call went out for volunteers for the Infantry.

Fred jumped at it, and was accepted into the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders, a

prestige regiment. Then a further call went out for men to volunteer as

scout/snipers. Fred jumped at it and reported to the selection board, which must

have been composed of retread officers from WW1.

Fred laughed when he told of his "selection". A piece of writing paper

was tacked to a post at about twenty-five paces. The candidates were given the

newly-issued Lee-Enfield #4 Mk. I rifles to replace the #1 Mk. III's they'd

brought from Canada. They were each given ten rounds of precious ammunition.

Each candidate was then to fire his full magazine load offhand at the piece of

paper as fast a he was able. The best shots from the group then became

scout/snipers, just like that. Selection and training all in one pass, with

little expenditure of ammunition!

I asked Fred how long it took him, and what was the size of his group at that

range? And whatever did rapid fire have to do with sniping?

Rather embarrassed, he said "maybe fifteen seconds, tops", and

indicated his thumbnail. Typical of the man. Rapid fire demonstrated that the

candidate knew how to use his weapon, and speeded up the process. Simple.

"Are you a cook, or a Rifleman?"

The selected went on to train in Scotland with the Lovat Scouts, stalking stags

in the Highlands, learning, if they didn't know already, the arts of the

ghillie.

Fred landed in France on D+2, June 8, 1944. He now carried the prized #4 Mk. I-T

rifle, mounted with the British 3X brass telescopic sight. Each sight was

especially mated to its own rifle. There was NO interchangeability. The scope

lenses were not coated. Shooting into the sun, or as far as forty-five degrees

to either side of it, the scoped blanked out. It also reflected a flare back to

the intended target. It weighed about two pounds with mount. It identified him

to a German sniper for what he was, that sniper's deadliest foe. Fred decided

very quickly to lose his. He was REQUIRED to use it, and having "lost"

it, was required to pay for it: about a month's pay! There were no more to be

had, so Fred "would just have to soldier on without it". He did so,

gladly.

Fred described his war in Normandy as a series of "walks in the

country". Close questioning revealed just what he meant by that. Battalion

HQ would be HERE. FAR forward of that would be his Company CP. Far forward of

that would be the fluid Front Line. About five miles beyond THAT, would be Fred!

Sometimes he had a partner, (he lost three to enemy action), but he preferred to

operate alone. Partners were always giving away his position at inopportune

times.

One day in my gun shop we were discussing the German Tiger tank. I opined that,

according to production figures in a book I had, there were very few in France,

most of them being employed in Russia. Fred said that on one of his

"walks", he'd found three of them together. Peering through a

hedgerow, he saw three Tigers, hatches open, sitting in a small field. The crews

were relaxing in the sunshine over breakfast. He said "I tickled them up

pretty bad, and they reacted pretty quick!" During the "tickling"

he must have exposed himself somehow, for all the quickly-manned turrets started

to turn toward him simultaneously. He said he was very glad the Tiger turrets

were hand-cranked, thus slow in traverse. He said the machinegun fire never

caught up to his scampering heels, and by the time the 88's blew his hedgerow to

pieces, he was long gone!

Fred said that when they were fighting through Caen, he was grateful for the

snipers' issue of rubber-soled boots. He said you could hear boots crunching on

rubble or broken glass from two blocks away. The trouble was, whose boots?

Theirs, or ours? "Sniper up!"

Most of his "work" was counter-sniper. A point man would be shot from

"somewhere". Fred would sneak up as close as he could get to the

fallen man whilst still under cover, and talk to his mates. Applying his

knowledge, he'd get a pretty good idea of where the German had fired from.

(Saving Private Ryan?) Then he'd wait. Eventually, he'd get his opportunity, and

the advance would continue until the next "Sniper up!".

So Fred soldiered on through France and Belgium, into Holland. He had a lot to

say about the Canadian Army supply system. He was never resupplied with uniform.

He came back to England in the same heavy woolens that he landed with on D+2.

The "grenade pocket" of the trousers was on the front of the leg. It

filled with sand during beach-assault training and nearly drowned him. Nobody

actually carried anything in it, because if you had to hit the dirt suddenly,

you'd get a very bad bruise on your leg. Most Canadian ammunition issued was of

very poor quality. He said that sometimes he couldn't have hit his hat with it

at fifty yards. American Winchester .303 was to be prized above all, if he could

find some. American rations were "great". The usual issue of

"rations" for his "walks" was a few choke-dog biscuits, hard

as nails. He always tried to conveniently be near an artillery unit at chow

time. He said they were the only ones who ever got hot food.

In this vein, I once mentioned that I had been acquainted with some vets from

Montgomery's famous Eighth Army of the Western Desert. They all vowed they would

never eat bully-beef again. Fred said he would have happily killed for

bully-beef. He never saw any.

He said that, after his rifle, his most important accoutrements were his shovel,

and his spoon, in that order. They were not available to mere infantrymen, so he

liberated them after coming ashore in France. He replaced the useless

entrenching tool with a real strong spade from somebody's garden in Caen. When I

showed him some of Mauldin's Willie and Joe cartoons on the subject, he broke up

laughing. He just loved Bill Mauldin's WW2 work! The spoon was brass, and came

from a Norman farmhouse. (Read: Dead German sniper.) It was German issue. He

showed it to me, swastika and all. He never carried any mess kit: too noisy. He

never carried anything that wouldn't fit in a very small pack: too bulky. No

blanket, no helmet. No gas mask, and no socks because there were none to be had.

The Canadians were assigned to sweep the left flank of Montgomery's creeping

slow advance, thus the stories of "Cinderella on the Left".

Fred could tell you all about the Battle of the Scheldt (Estuary)!

The American forces were not to encounter such conditions until Vietnam, and

THEY got to do it in a warm country!

The polders were mined, then flooded, so our troops had to advance along the

dikes. The dikes were heavily fortified, and machineguns could sweep them clean

with ease. It was pure hell, cold, wet, and deadly. Fred was tasked with

clearing the gunners off their weapons until some brave man could get within

grenade range. Would you, with a bolt-action rifle, willingly engage entrenched

machinegun crews who knew exactly where you were? Of course, they never gave him

a medal for that work! He was "just doing his job". Maybe those old

boys with the rapid fire requirement back at selections knew something? Typical

Fred.

Fred got blown up during the Scheldt campaign. From the waist down he was amass

of scar tissue, which he was too tired to hide when I visited him during his

last days in hospital. Having risen to the rank of Sergeant, and been so

incautious as to allow himself to be hurt to the extent that he was of no more

use to the Army, he was quickly reduced to Corporal, and started home. Aid

station. Nothing they could do. I mean NOTHING. A few bandages and no pain

relievers. A truck ride further to the rear, SITTING on a wood bench over

shell-pocked mud roads. Nothing they could do there. Two days wait. A three-day

ride across the Channel IN A FLAT-BOTTOMED OPEN LANDING CRAFT returning with

faulty engine for repairs. Fred said it was the salt spray coming over the side

that kept his wounds from turning septic, and never mentioned what salt felt

like on raw flesh.

Hospital at last. A few weeks, and they turned him out to recuperate on his own.

He got to see a little of Britain up around Manchester. Finally he was boarded

onto a ship for Canada, and after an interminable trip breasting the westerly

gales, landed, and was given crutches and put on a train for Calgary Alberta,

his place of enlistment. There, he was to report to the Colonel Belcher Military

Hospital for further treatment.

Seven days on a hard horsehair coach seat later, he arrived in Calgary. His car

was positioned such that he had to crutch the 500 yards to the station along the

roadbed. Once in the station, as there was no one there to greet him, he was

directed to the Col. Belcher on 4th Street, eight blocks away.

He made it, probably on pure grit. Up the steps to the main entrance, and in to

the reception area. "I'm sorry, Corporal, but we have no orders about you.

You can't be admitted without orders!" (His orders were supposed to have

been mailed from his port of arrival upon landing, so he would not lose them

while traveling, to reach Calgary long before he did. Didn't happen.)

So there's Fred, alone in a city he hardly knew, without a penny to his name. He

said he just sat down on a bench in the park across the street and tried hard

not to weep. Knowing him, he did not.

A passing angel of a woman widowed by the war saw him, forlorn on his bench

probably looking like death-warmed-over, and prodded his story out of him. she

forthwith took him into her home some short blocks away, and marched back to the

Col. Belcher to inform them where he was. He was in her home for two weeks

before his orders caught up to him and he could be admitted for treatment. He

stayed a week, went to the local HQ in the Armories, took his discharge and

hitchhiked home to Brooks.

Fred, like many Canadian vets, vowed "Never Again!" His military

career left him bitter to his dying day, and with an absolute hatred of

officialdom in Ottawa.

He was back in Calgary in 1947, riding as an outrider for one of the better

wagons in the famous Chuckwagon Races of the Calgary Stampede. He lived through

that, too. Before OHSA and the Humane Society got hold of things, "the

Chucks" were pretty hair-raising events, with wrecks galore. Today, they're

pretty tame. Then he went back to just "cowboyin'", a valued hired man

on one ranch or another, shooting as and when he could afford a new gun or

ammunition.

When Fred finally decided to give up the life in his seventies, he came north to

Monitor, Alberta, and bought acreage and a house on the north side of town,

living on his scant savings and Government pensions. He kept and rode the odd

horse once in a while, and shot in the local gravel pit, a lot.

In 1988, when I opened my little gun shop here in the village of Veteran,

thirty-odd miles west of Monitor, Fred was one of the first in the door. We hit

it off immediately, and became fast friends. It was very apparent to me that,

unlike most of the locals, here was man man that understood riflery! We soon got

into the discussions of where and how to put in a formal shooting range

facility. One of my customers, Bob Lindsay, said he might have such a place, if

his father Bill would consent. Fred and I went to see Bill. Bill was very

impressed with Fred, less so with me, the city guy, but he gave his consent and

the project just "growed like Topsy". I used my engineering skills to

design and lay out various facilities and ranges to fit the land with minimum

alteration and maximum utility.

I'd met Will Porter, a young man then in his late twenties, of the Double U,

Quarter Circle ranch. His father was still alive then, and let Will bring his

huge Cat down to Lindsay's to push a little dirt. Boy! Did we push dirt! I

won't go into all the details of the years of progress here, as we have

explanatory photos of the finished Ranges. Fred was everywhere during all this,

cadging materials and cajoling donors, and enlisting members for the new

Nosehills Gun Club. One weekend, with almost no help, he posted and strung about

800 yards of three-strand barbwire fence, with gates, to seclude the main area

from roaming cattle. He was eighty-two at the time!

It was about 1995 that Fred's arthritis (from the polders of Holland?) began to

really drain him. He could no longer shoot his beloved rifles offhand, and had

to content himself with working from the benches, or the rifle pits we had

emplaced. His handgun work eventually had to be given up: his hands were no

longer strong enough. Every winter, pneumonia sent him to hospital. He hated

hospitals! If he was in any kind of shape, he'd come to our house for Christmas

dinner. My kids treated him like a grandfather, my own father

having died when I was very young.

When the ranges were set up for Metallic Silhouette competition, Fred became

interested in that facet of the shooting sports. From a Lee-Enfield #4 Mk. II, I

cobbled him the be-all and end-all of Silhouette pistols,

"Shorty-the-Brit". I wonder (Ha Ha!) if he ever registered it?

"Shorty" improved quite a bit on his Martini-Henry shorty pistol that

he picked up at some auction somewhere for about ten dollars!

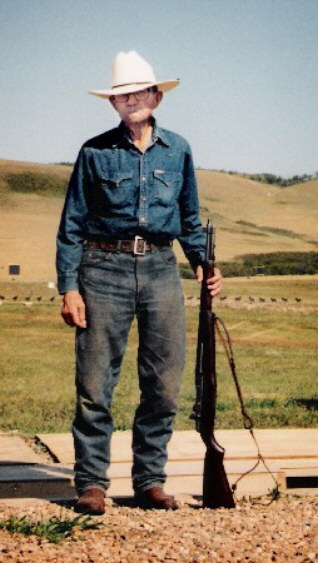

As noted elsewhere, Fred was the first in the Club to clean the Military Match,

and he did it with his M1, in fourteen shots out of the twenty allowed. He

was eighty-eight, and we have a photo taken that day of him with his

rifle. It hangs in a place of honor in the clubhouse.

Fred was forever at the Ranges. In his final years he was living in the Seniors'

Lodge in Consort, Alberta, between his home in Monitor and my home in Veteran. I

visited him, and he visited me. He also visited other friends, and there was

always his good friend and neighbor Don Rudd to drive him wherever he wanted to

go. Fred had long ago converted the top floor of his house to an HO model

railroad layout of some immensity, and if you called at his house you would

often find him up there, running his hand-built trains. An artist of some skill,

he once presented me with a little pencil sketch of an old cowboy holding a

coiled rope, which I treasure. He'd doodled it whilst talking, in the gun shop,

probably thinking of his life on the range.

Fred was forever at the Ranges. In his final years he was living in the Seniors'

Lodge in Consort, Alberta, between his home in Monitor and my home in Veteran. I

visited him, and he visited me. He also visited other friends, and there was

always his good friend and neighbor Don Rudd to drive him wherever he wanted to

go. Fred had long ago converted the top floor of his house to an HO model

railroad layout of some immensity, and if you called at his house you would

often find him up there, running his hand-built trains. An artist of some skill,

he once presented me with a little pencil sketch of an old cowboy holding a

coiled rope, which I treasure. He'd doodled it whilst talking, in the gun shop,

probably thinking of his life on the range.

Fred was a most courteous gentleman, polite to everyone. If you were a fool or

an idiot by his standards, he would have absolutely nothing to do with you. You

always knew where you stood with Mr. Bragg! I believe that hardly a day went by

that he was not peaceably armed with his 1911 .45 tucked somewhere about his

person. Sometimes forgetful in his advanced years, he left said.45 on the bed in

his room one day, to be discovered by the cleaning staff. Heavens to

Murtgatroyd! What to do? The local Mountie was called to safely remove the

offensive weapon. Fred was "granted an interview", promised to be

good, and got his .45 back. Authority was assuaged: they had done something.

Of course, Fred went right back to packin' his piece, and the Mountie knew that

he did. Around here, we all know, as did the Mountie then, that disarming Fred

and living to old age were mutually impossible scenarios. Fred quietly gave away

all his many guns shortly before his death. I don't know who got the 1911. I got

his Woodsman Match Target.

The Fall of 2001 came in early, cold, and wet. Fred was taken from the Lodge one

night to hospital. He received the most excellent care. They tried their very

best, but the old Rifleman was too weak. He died October 26.

He was laid in his coffin dressed simply in his blue jeans and denim shirt, with

his Queens Own tam and his medals on his chest. The Canadian Legion

representatives gave him a final salute. At the graveside, so did I.

We buried him in a military grave in the cemetery of his home town of Brooks,

with a piper playing his favorite airs, and finally, Amazing Grace, and I cried

like a baby, as I am now, writing this. I guess I'm getting too emotional, now

I'm past seventy.

Thus, Fred Bragg.

Colonel

Cooper once wrote that the proper aim of a young man was "To Ride, Shoot

Straight, and Speak the Truth". Well, Colonel, here was a man who did it

all in spades!

With much respect,

Vic Hatheway

Note: Any errors in this biography are mine. Fred seldom elaborated on his life,

and the above are my recollections of driblets of information strung together

the best I know how.

|

Upcoming Events

Please watch here for workbee's, corporate shoots, area gun shows, advertised shoots etc.

Forecast

|